After Image: between the subject, the camera, computation, and representation

An Adaptation of my 2019 Thesis paper for my MFA in Design and Technology at The New School, Parsons School of Design

A thank you to my Thesis advisors, Marisa Jahn and Loretta Wolozin. And a huge thank you to The Studies in Tamil Studio Archives and Society.

Abstract:

What is the aesthetic and analytical potential for machine learning to reveal semantic or visual patterns from large photographic archives? What are the challenges and caveats of working with machine learning in the archival context, where naturally anthropological, historical, and cultural aspects come into play? And finally, once patterns are identified, how can they complement or shed light on research around shifting values for representation of self and family in colonial and then postcolonial contexts in the East?

After Image is an art installation comprised of a video piece and creative data visualization both showcasing a series of experiments done with an archive of the artist’s own family photographs in relation to a larger archive of South Indian studio photographs from the Studies in Tamil Studio Archives and Society (S.T.A.R.S). Each of these experiments employs machine learning and computational techniques to sort, average, and analyze the images in order to surface semantic and visual patterns across the hundreds of images. Through the use of these techniques, the artist performatively questions the notion of collective and individual identity, and highlights the complexity of the image as a data point.

— — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — —

“The photograph is a multiplicity of different things: a way of speaking, a way of showing, a recorded point of view, a piece of visible architecture, a force that is exerted on the viewer, a seduction, a coercion, an exercise of power that has an effect on how the self is fashioned.^1”

- R. Srivatsan from Conditions of Visibility: Writings on Photography in Contemporary India

— — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — —

Chapter 1 Introduction and Impetus

Concept Statement

After Image is an art installation comprised of a video piece and creative data visualization both showcasing a series of experiments done with an archive of the artist’s own family photographs in relation to a larger archive of South Indian studio photographs from the Studies in Tamil Studio Archives and Society (S.T.A.R.S). Each of these experiments employs machine learning and computational techniques to sort, average, and analyze the images in order to surface semantic and visual patterns across the hundreds of images. Through the use of these techniques, the artist performatively questions the notion of collective and individual identity, and highlights the complexity of the image as a data point.

Representation of Self and Family in The Family Photograph

My maternal grandmother’s house in Besant Nagar, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India, is where, as a teenager, I began to digitize family photographs that were starting to disintegrate from age and climate. These photographs, portraits of children and families, photos commemorating events like graduations and marriages, and of course the passport photo, all became part of an understanding of my family history and culture as I grew up here in the United States. The family photograph as a source of data interests me in that it is such a traditional and personal form of archival practice, and yet it has the potential to reveal information in a broader context around a shared identity or cultural history. One might say that it could feel a bit strange to look at such an intimate artifact within a broader context, but especially in the case of a diaspora (i.e. the South Asian diaspora), there can be something significant in finding a shared aesthetic in personal archival material. It can help solidify a sense of community. This is part of the intent of archives such as SAADA (South Asian American Digital Archive) who believe that “archives can be dynamic spaces for dialogue and debate” and are “vital to community wellbeing.”^2

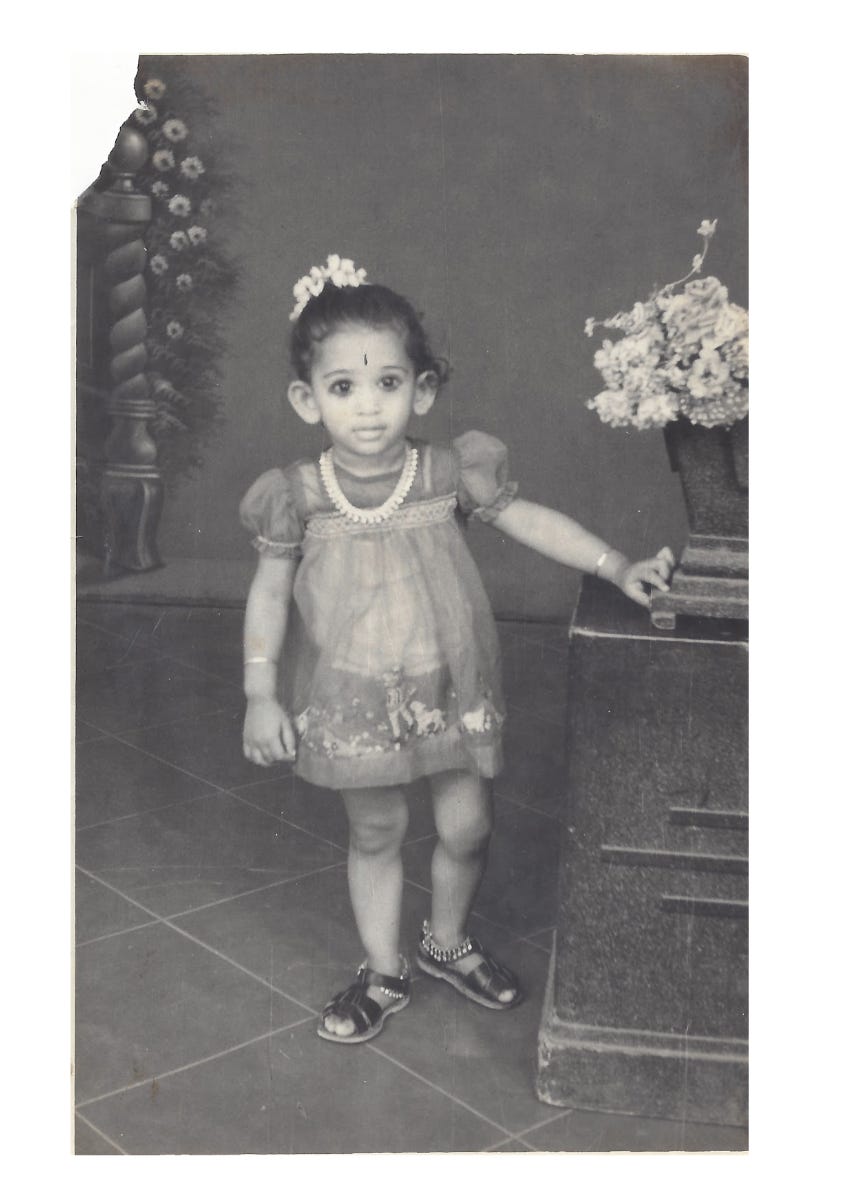

And this feeling of community is one that I have when looking through images from the Studies in Tamil Studio Archives and Society. The Studies in Tamil Studio archives and Society (S.T.A.R.S.) is an interdisciplinary group based in Pondicherry, India that has assembled the first ever archive of commercial Tamil studio photography.^3 They’ve been collecting images taken in Tamil studios between 1880 and 1980. Many of my own family photographs were taken in Tamil studios within this time frame, and visually, the similarities are apparent (see fig. 1 & 2). Patterns across the use of props, pose, and composition start to emerge from the archive of hundreds of images and form a larger identity around the ways in which we represent ourselves and our families.

The fact that the S.T.A.R.S. archive contains so many portraits and family photos is important for reasons that go beyond familiarity for the South Asian diaspora. This archive is important also because there is a lack of study around this type of image in relation to the history of photography in India. Generally the focus tends to be either ethnographic images taken during the British Raj for the European gaze, focussing particularly on documenting socio-racial categories (especially with postcolonial studies), or images of Indian elites and royalty. However, between the 1880s and 1980s, many photographs were produced outside the elite and colonial contexts in Indian-owned photography studios.^4 Being the first Tamil Commercial photography archive, S.T.A.R.S. creates a new opportunity to study these images at large. And these images are also a rich source of information in that prior to the 1990’s, owning a camera in the household was still quite uncommon and so the photo studio was, for many Indians, “the dominant institution of popular photography” for over 100 years.^5

Figure 1, My mother

Figure 2, photographs from S.T.A.R.S.

A Close and Distant Reading

In the field of the Digital Humanities, many are exploring the potential for machine learning to surface patterns. Distant Reading, a term coined by Franco Moretti, co-founder of Stanford’s Literary Lab, refers to the use of computational methods to analyze large amounts of data.

And while the majority of the Lit Lab’s projects obviously deal with the computational analysis of literature, one particular project looks at images. The study entitled Totentanz, looks at Aby Warburg’s famous Atlas Mnemosyne, a collection of 71 panels of approximately 1,000 images (paintings, book pages, stamps, illustrations, etc) arranged in a particular fashion aimed to “make visible — through the shock of a gigantic montage — morphological similarity across historical time.”^6 The arrangement of the images is a bit cryptic but one decipherable thread amongst the images is Pathosformel, a term coined by Warburg meaning a passionate/emotional gesture. Pathosformel was the focus of the study as researchers focussed on depictions of the human body in the images of the Atlas, looking specifically at pose and using clustering algorithms to decipher if there was indeed a recognizable ‘pathosformel’ in some poses vs others. In viewing these clusters, one can see that there is “a dissonance is inserted between the upper and the lower part of the body” as in the poses identified as fitting pathosformel seem to involve a multiplicity of actions in opposed to a fluid singular movement from all parts of the body.^6

Figure 3, A contrapposto pose (no pathosformel)

Figure 4, a pathosformel pose

While Aby Warburg’s Atlas is highly subjective in its arrangement I think that the combination of quantitative and qualitative measures in analyzing the images is key here. While I think distant reading can provide some interesting perspective on similarities across large amounts of data, I think it is most useful in combination with “close reading” or a more in depth, smaller-scale human driven analysis.

And this was the approach I took with my thesis project in implementing Machine Learning in the sorting of images from both my family album and the S.T.A.R.S. archive. I will get into more depth about my exact methodology in the next chapter, but essentially I am interested in how the patterns surfaced through a distant reading of these images could complement or interact with a more intuitive reading of the hyper-personal data at hand.

Chapter 2 Methodology

Mapping the Models

My process combined the use of pre-trained models and manual editing to sort the photographs according to similarity. I was interested in identifying aesthetic continuities or threads across certain images. For the images around the central video component, Tensorflow’s Imagenet model was used to create groups around similar subject matter. For the video component, pose detection and object detection are used to create visual overlays indicating the “machine interpretation” of each image.

Once the clusters were created using machine learning, I manually edited the clusters for outliers or what I perceived as incorrect groupings. Although manual editing was definitely a laborious part of the process, the initial seed of each cluster very much came from the computational methods as oppose to my own interpretation. The labor involved in manually editing the clusters was mostly due to the arguably poor performance of the pre-trained models I used.

Pre-trained models such as YOLO (You Only Look Once) or OpenPose are open source machine learning models that have already been trained on a dataset of images usually from other sites or services on the internet. In the case of YOLO, which is an object detection model from the University of Washington, it “learned to see” through the COCO dataset, labeled images taken from Flickr.^7^ 8 Whereas, with OpenPose, which identifies human poses, training data was compiled from screenshots of Youtube videos.^9^ 10 While the use of pre-trained models is extremely helpful in that it allows one to skip the laborious and expensive process of sourcing training data and training a model from scratch, being wary of what training data is used to teach a model to recognize objects, poses, etc. is important because it can give insight into possible potential biases that may affect the performance of the model on certain types of images over others (see Figure 5). For instance, most of the images in COCO are born-digital, color, and taken after the year 2000. The images I am working with are very different in that they are analog, mostly black and white or sepia photographs from South India. The performance of these models on the S.T.A.R.S. images is poorer than with images that look more similar to the original training set from Flickr. For this reason, I had to manually adjust the groupings myself in many cases. In an ideal world, I would have a pre-trained model that was trained on early studio photography from the 1800’s, however, sourcing enough images and doing the training is beyond the scope of myself and this project but is definitely something I am considering for the future.

Figure 5, Mapping the pre-trained models used

Findings

In terms of themes across composition and subject matter pulled from the clustering of images, interesting details surface around the notion of westernization and also ideals around intimacy in relationships. Through further research into these photographic conventions, I also realized that rather than trying to define a South Indian style of photography in terms of distinction from Western conventions of photography, it is much more productive to take a more nuanced approach, thinking about the ways in which western aesthetic conventions were remixed, appropriated, and ultimately transformed within the east.

Additionally, through researching studio photography in other postcolonial contexts, I actually found many through-lines between the images from S.T.A.R.S. and studio photography in Africa. This mirroring of photographic practices in Africa and India is illuminating for me. On some level, it speaks to the cultural exchange between these places (there is a large Indian population in African countries, particularly on the east coast), but it also shows the ways in which grapplings with colonial and then postcolonial identity manifest in the portrait photograph. In retrospect, this makes a lot of sense in that the ways in which we choose to represent ourselves and our families are reflective of shifting cultural ideals around westernization and what is upheld as part of modernity and progress.

The East, The West, and the Modern World

One aesthetic trend visually surfaced in my research is that many of these studio photographs exhibit compositional characteristics that conform to “victorian aesthetic norms” with the use of “painted backdrops of aristocratic interiors”, and poses in which the subject is leaned against a pillar or pediment.^11 The painted backdrops at this time could be ordered from England, or hand painted. In fact, many of the backdrops that were hand-painted were copied from catalogues used to order the backdrops in the first place. Many photographers who opened studios in India were first working as painters and so were very skilled in hand painted backdrops but also in overpainting of photographs and touch-ups on negatives.

The leaned pose where the subject is leaned against a table or pillar has technical origins in that early photography required long exposure times and so these poses served a dual purpose in that they allow the subject to stand comfortably for a long amount of time without appearing strained.^12 We can see this type of pose in one cluster of images featuring mostly children positioned leaning against side tables with flowers (see Figure 6). While the use of flowers as decoration also can be placed as part of European aesthetics, flowers are also a large part of Indian culture, used in rituals, celebrations, and daily life. In Heike Behrend’s Love A La Hollywood and Bombay In Kenyan Studio Photography, a similar idea of the flower arrangement holding dual significance in both local culture and also being from European influence is also brought up. Behrend discusses the fact that you will rarely find Kenyan studio photographs without the use of a flower arrangement.^13 After working with S.T.A.R.S. and my own family photographs, I would say the same for these images as well. Flowers, whether painted in the background, or as props are present in almost all of the images that aren’t cropped around the face or shoulder level.

Figure 6, Three S.T.A.R.S. images from one cluster

Other props that are used are often meant to signify a sense of modernity and wealth. Everything from western clothing (for men or children, as women are mostly in saris), to the inclusion of objects such as wristwatches, books, and handbags are used to make the subjects appear more modern or to denote education, class and/or wealth. In one photograph we even see the playful inclusion of a briefcase and painted backdrop to give the appearance that the couple is well-traveled, worldly, and wealthy (see figure 7). South Indian studio portrait photography re-contextualized aesthetic tropes from European photography as signifiers of social class, education and style.

Figure 7, A photograph from S.T.A.R.S. of a couple

Figure 8, A portrait from S.T.A.R.S. of a man holding a paper

Figure 9, A portrait from S.T.A.R.S. of a man holding a book

Figure 10, A portrait from S.T.A.R.S. of three women

Couples

Another important aspect that can be analyzed through the clustering of the S.T.A.R.S. images is the depictions of couples and the ideals around marriage and intimacy. For instance in Figures 11, 12 , and 13, we see the same pose where the man in the couple is casually leaned over the wife sitting. Figure 11 is a marriage photograph of my grandparents taken in 1933 (my grandmother was 12 and my grandfather was 19). Figure 12 is from the S.T.A.R.S. archive and finally, figure 13 is actually a Kenyan studio photograph taken in 1956.13 In Behrend writes about this particular Kenyan photograph, illuminating this particular archetype of pose in the colonial context within which there are perhaps complex views on intimacy and marriage due to European influence and local custom:

“The woman and the man in front are positioned carefully in the center.

There is an attempt to give the impression of being casual, the man

generously leaving the chair for her while sitting on the armrest. His

gentlemanly generosity, however, elevates him in relation to her. He

possessively embraces her, indicating their sexually charged love

relationship, while she sits in her chair with her legs crossed and flowers

in her hand.”^13

I reference Behrend’s writing here because I feel it speaks to the other two photographs as well in that this intimacy in pose is significant in contrast with some of the other archetypical marriage poses where the subjects are at a much more acceptable distance in the eyes of what one might consider a more conservative approach to display of sexual or physical intimacy. The casualness of these images suggests a desire to appear more conforming to European ideas around love at this time in order to evoke a sense of modernity. It also reveals cultural customs around marriage itself. The idea of a “love marriage” or a marriage within which the couple is not arranged by family, or motivated by social or economic reasons is something that is arguably at this time, reserved for an upper class. Romantic love is idealized in the West and thus a privilege in the East.^13

Figure 11, My paternal grandparents’ marriage photo from 1933

Figure 12, A portrait of a couple from S.T.A.R.S.

Figure 13, A portrait of a couple taken in a Kenyan photo studio in 1956

In contrast with these images, Figures 14 and 15 show a couple with much more physical distance from each other. If they are not separated by space, they are definitely not gesturing towards each other in any way to suggest a physical or emotionally romantic relationship. Overall the poses are much more modest and defer to the ideals of Indian society around the appropriate public display of intimacy.

Figure 14, A portrait of a couple from S.T.A.R.S.

Figure 15, A portrait of a couple from S.T.A.R.S.

Unknowns

And finally in some cases, I was completely in the dark about potential reasons for aesthetic similarity in photographs. For instance, several images featured the same style of round rattan chair (figure 16). It’s possible that these chairs were simply in style and in wide production in Tamil Nadu during the time these photographs were taken, but aside from this speculation, I am unsure of the reason for this similarity.

Figure 16, Two S.T.A.R.S. photographs from round rattan chair cluster

Chapter 3 Methodology to Form

In deciding on how to translate this research into a physical form for exhibition, I considered the interaction between the viewer and the archive and also the balance between the computational viewing of these images and the personal nature of the photographs.

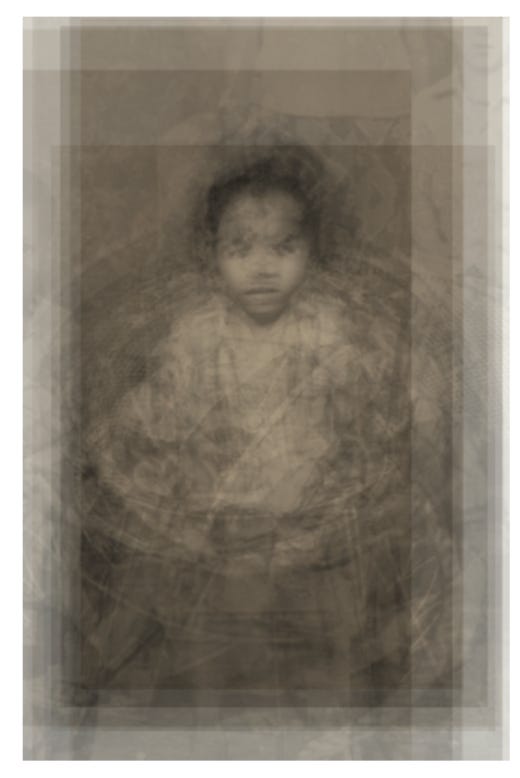

I created an archival table, using the top surface to showcase the computational image clusters, as well as an embedded video in the center (see figures 17 and 18). The clusters created by subject matter are represented around the central video component in the form of an intricate mapping of images. Each group is represented by a cluster of its individual images around a central node image, which is a computational averaging of all the images within the cluster (see figures 19 through 23). Node images are a bit lifted onto a layer of clear plexiglass, further distinguishing them from the individual images. On a second layer of plexiglass, representations of “machine vision” are overlaid onto the individual images in each cluster. These representations show lines indicating pose, circles indicating areas of high exposure and contrast, and finally rectangular boxes indicating objects. Boundaries between clusters are represented by white lines that can be traced if one chooses, but overall, the clusters are meant to engulf one another in a complex layout. The viewer is meant to spend time with the images in order to fully decipher the clusters. A magnifier is provided for the viewer to further investigate individual images or nodes, not only encouraging the viewer to linger, but also referencing the tools of archivists, such as pocket magnifiers used to examine lantern slides.

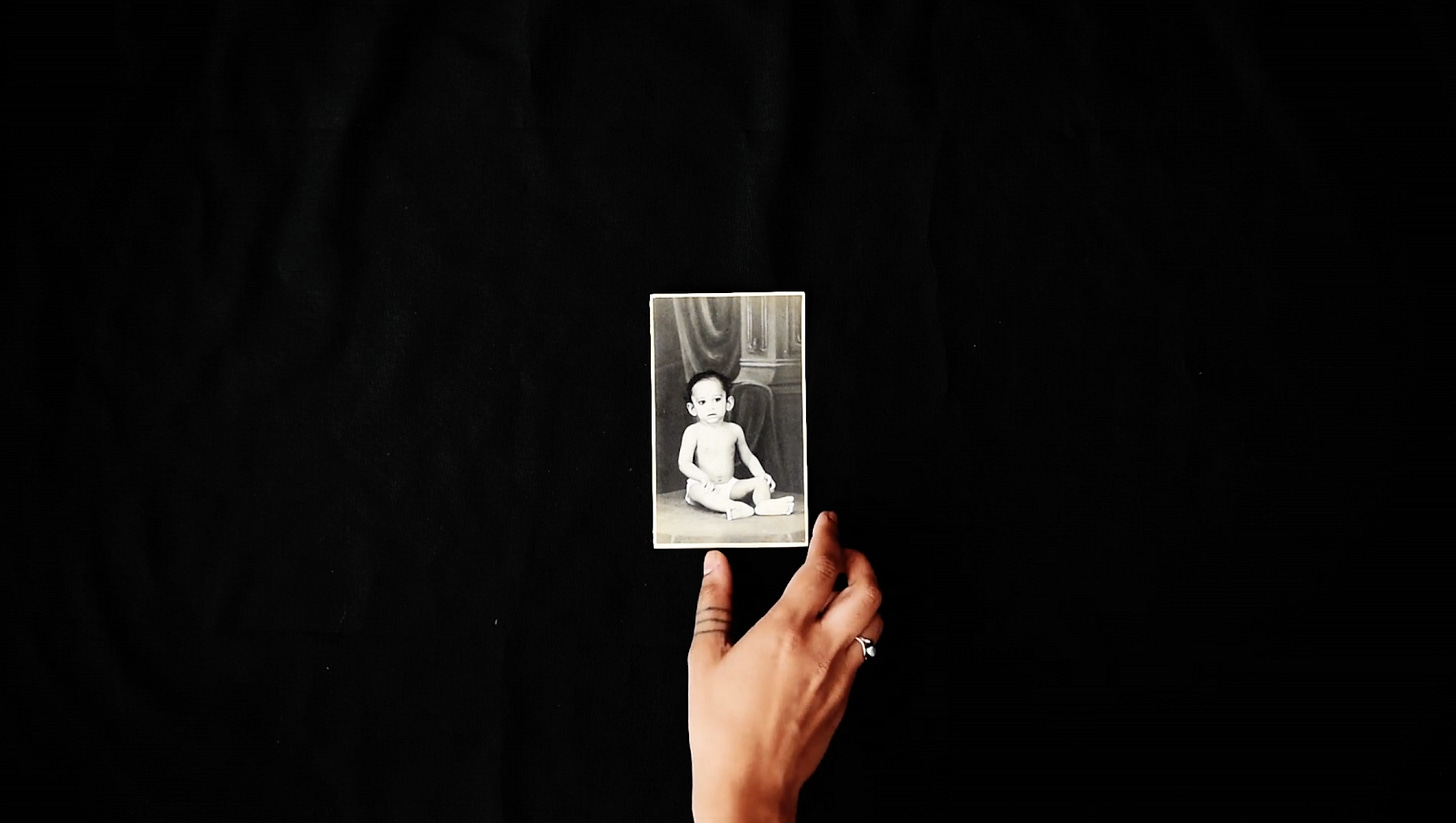

In the center on loop, a video shows me placing my own family photographs centrally, triggering the flashing of similar images from the S.T.A.R.S. archive on the left, and on the right, their corresponding machine overlays indicating pose and object detection (see figures 24 through 26). This video component disrupts the complex interweaving of the clusters with a more personal element that is the hand of the artist and the materiality of the physical family photographs in contrast with the scanned images. One can see through the physical placement of the family photos, that some are wrinkled or even torn, feeling more like artifacts than digital data. But in its disruption, the video does not create a stark dichotomy between the computational sorting of the images and the human, physical handling of the family photos, but rather centers the hyper-personal as the focal point, or primary nexus from within which the computational research is then forged.

Figure 17, Installation view

Figure 18, Installation view

Figure 19, Top view of the layout of the clusters with the video in the center

Figure 20, Diagram of top view of the layout of the clusters with the video in the center

Figure 21, An example of an averaged image cluster

Figure 22, An example of an averaged image cluster

Figure 23, A close up of a cluster

Figures 24, 25, & 26, Stills from the central video

Bibliography

1. Srivatsan, R. “Conditions of Visibility: Writings on Photography in

Contemporary India.” Kolkata,

India: Stree, 2000.

2. South Asian American Digital Archive, “Mission, Vision, and Values”, saada.org,

www.saada.org/mission (accessed Dec 2018)

3. Butterworth, Jody, “Representing Self and Family. Preserving early Tamil Studio Photography

(EAP737)”, Endangered Archives Programme at the British Library, eap.bl.uk/project/EAP737

(Accessed November 2018)

4. de Parscau, Pierre, “Photo Studios: Vanishing Windows Through Time”, Documentary Film, Paris,

France: CNRS Images, 2018

5. Mahadevan, Sudhir. “Archives and Origins: The Material and Vernacular Cultures of Photography in

India”, Trans Asia Photography Review Vol 4, Issue 1: Archives, Fall 2013

6. Impett, Leonardo, and Franco Moretti. “Totentanz. Operationalizing Aby Warburg’s Pathosformeln”,

Stanford Literary Lab, November 2017, litlab.stanford.edu/LiteraryLabPamphlet16.pdf

7. Reddie, PJ, “YOLO: Real-Time Object Detection.”, pjreddie.com, pjreddie.com/darknet/yolo/,

(Accessed November 2018)

8. COCO Consortium, “Common Objects In Context”, COCO consortium, cocodataset.org (Accessed

November 2018)

9. Cao, Zhe, Gines Hidalgo, Tomas Simon, Shih-En Wei, and Yaser Sheikh, “OpenPose: Realtime

Multi-Person 2D Pose Estimation using Part Affinity Fields”, arXiv:1812.08008v1[cs.CV], Dec 18,

2018, (Accessed January 2019)

10. Max Planck Institut Informatik, “MPII Human Pose Dataset”, Max Planck Institut Informatik,

human-pose.mpi-inf.mpg.de/, (Accessed January 2019)

11. Wendl, Tobias. “Entangled Traditions: Photography and the History of Media in Southern Ghana.”

RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, no. 39 (2001): 78–101.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/20167524.

12. Fabry, Merrill. “Now You Know: Why Do People Always Look So Serious in Old Photos?” Time

(November 28, 2016), time.com/4568032/smile-serious-old-photos/ (accessed March 29, 2019)

13. Behrend, Heike. “Love á La Hollywood and Bombay in Kenyan Studio Photography.” Paideuma 44

(1998): 139–53. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40342027.

MacDougall, David, and Judith MacDougall. “PHOTO WALLAHS”, Documentary Film, Canberra, Australia: Ronin Films, 1991

Madhav Prasad. “Reading the Photographic Image.” Economic and Political Weekly 36, no. 10 (2001): 840–41. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4410374.

Tillotson, Simon. “The Invention of Photography.” BBC Radio, In Our Time. Pocast audio. July 7, 2016. www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b07j699g

Walter, Benjamin. “A Little History of Photography.” (1931) In On Photography, edited and translated by Leslie. London, United Kingdom: Esther. Reaktion Books, 2015

MacDougall, David. “The Corporeal Image: Film, Ethnography, and the Senses.”

Princeton, NJ, U.S.A. : Princeton University Press, 2006.

Joshi, Bharat R. “UNVEILING INDIA THE EARLY LENSMEN 1850–1910 by

Rahaab Allana, Davy Depelchin.” New Delhi, India: India International Centre Quarterly, vol. 41, 2014.

Chowdhry, Jennifer. “Deepali Dewan, Embellished Reality: Indian Painted

Photographs: Towards a Transcultural History of Photography.” Toronto, Canada:

Royal Ontario Museum Press, 2012.

Stanford Vision Lab, “Imagenet Dataset”, Standford University, www.image-net.org (Accessed November 2018)

Tensorflow, “Inception.”, Github, github.com/tensorflow/models/tree/master/research/inception, (Accessed November 2018)